A better broiler

Nova Scotia hatchery selling chicks bred for free-range production

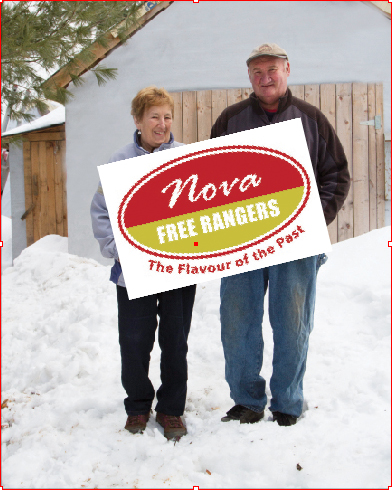

Barbara and Brian Aaron have started a hatchery in Lunenburg County, N.S., to supply Nova Brown broiler chicks, specifically targeting free-range producers. (David Collins photo)

by David Lindsay

The breeding of highly efficient commercial broiler chickens has come a long way. Based on the industrial model of converting poultry rations into meat, great strides have been made. But if you have ever raised a batch of those commercial meat birds using free-range methods, you may have observed that they prefer to live out their days taking as few strides as possible. In fact, they tend to stride over to the feeder and stay there. Foraging for wild food is not high on their genetically programmed to-do list.

Barbara Aaron and her husband Brian, of Rhodes Corner, N.S., are about to hit the market with a new breed of meat chicken that shows more initiative in feeding itself. In the 1990s the couple was involved in the selection of stock from Europe for a free-range growers’ group in Scotland. In 2013 they returned to Nova Scotia, and set about establishing a breeding flock based on the same bloodlines. Calling their business Nova Free Rangers, they have been taking orders for day-old Nova Brown chicks, which will be available this spring.

“We had a hatchery in the UK, and we used this bird from egg to plate, because we were involved in the processing plant too, so it’s a bird that’s really dear to my heart,” says Barbara. “I really feel that the Canadian consumer deserves a choice of the bird she’s eating. Right now she has no choice. It doesn’t matter whether you buy in B.C. or Newfoundland, it’s the same white bird.”

The Nova Brown is a red-feathered chicken derived from crosses of pedigreed heritage lines. It’s a hardy bird, specifically bred for outdoor production. “They don’t have the problems that are associated with the white industrial bird,” says Barbara. “You do not have leg problems. Because they’re on a slower diet, you do not get heart attacks. They don’t keel over like the white birds do.”

MEDIUM GROWTH

Some heritage breeds produced for the European free-range market cannot be slaughtered before 81 days, but the Nova Brown would be considered a medium-growth bird, expected to reach six or seven pounds liveweight at 63 days, which is equivalent to a dressed weight in the range of 4.5 to 5.5 pounds. Barbara says some males may be a bit bigger. She believes this growth rate makes the bird economically viable for specialty producers here. Moreover, she says, it will “finish like a good broiler should,” and the quality of the meat will win over customers.

“I’ll admit I’m prejudiced, but the taste of the white bird that you’re buying in the store, if you don’t put a sauce or something on it, you would be hard pushed to know that it was chicken. People deserve better than that. Because these birds are from the old, traditional breeds, you’re getting that old-fashioned flavor. The taste is so different, so European.”

The couple have built a barn for the breeding flock on their six-acre Lunenburg County property, and in mid-May the birds will be at week 26, when they start laying hatchable eggs. Once the birds are in full lay, the operation will be supplying about 300 chicks per week for growers in Nova Scotia and beyond. To maintain a consistent production level, an overlapping flock must be reared to come into lay as the first flock declines.

“It involves a fair amount of investment,” says Barbara. “We are intending to put further barns up. We’re hoping that this first flock goes well, and then we would obviously look at expanding.”

The target market for Nova Brown chicks includes small flock keepers who raise chickens for personal consumption, but Barbara especially hopes to supply chicks for commercial free-range growers, including those that are certified organic. In Nova Scotia, free-range licensees are allowed to produce up to 10,000 broilers a year without holding quota, though they must pay fees and levies to the marketing board.

“The chicken board is really helpful to the free-range growers here. They understand there’s a place for free-range chicken in the market,” says Barbara. “I have to give them kudos for that. I have to say that’s great for Nova Scotians. The only other place (in Canada) that gives the free-range bird any leeway at all is B.C. Ontario is terrible.”

SEASONAL PRODUCTION

One of the restrictions on licensed free-range growers in Nova Scotia is a limited production season, which prevents them from raising chickens between November and April. “That affects us because our breeders will stay laying,” says Barbara. “We have to fill that gap somehow. We may have to go out of province.”

The couple do not intend to raise broilers commercially, but they have considerable experience doing so, and will gladly provide production advice for their chick customers. One of the things they stress, in addition to the usual admonitions about good hygiene, is to provide the birds with mixed range.

“All chickens, no matter what kind they are, have a fear of overhead predators – an inborn fear, from the old jungle fowl that they are derived from,” says Barbara.

“If you show a bird a wide open field, probably it will be very reluctant to go outside. In Europe they really push having a varied range with bushes. Orchards are excellent. A lot of the woodland trusts over there – which are like our Crown lands – they rent those out for the chickens to go in. So we would always encourage growers to definitely have a grass area, to have dusting baths in a nice dry place somewhere, and have shrubs and whatnot.”